Using a Paris postcard as an ideological contrast, Whitney O’Reardon (Class of 2022) suggests how Pissarro embedded politics in his rendering of an urban crowd at Gare St. Lazare (1893).

This essay won the Friends of Art Award, 2021 for outstanding written work in History of Art. Whitney O’Reardon researched and wrote an earlier version for Professor McBreen’s Modernism and Mass Culture in France 1848-1914.

The Gare Saint-Lazare in Paris was an icon of urbanism that Impressionist artists used to capture the changing nature of modern life. By the early 1890’s, Paris was well established as a modern capital. Its population had grown exponentially. Medieval neighborhoods had been razed and rebuilt, and new public amenities like shopping centers and entertainment halls were alive with activity, enabled by train stations like Saint-Lazare which encouraged both travel and commerce.

This essay will focus on two images: Camille Pissarro’s Cour du Havre (Gare St. Lazare) (1893) and a postcard depicting the same location, c.1907-1914 [Figures 1, 2]. Unlike earlier Impressionist portrayals of Saint-Lazare, most notably by Monet, these two works do not feature train cars or the railways; they both depict the station’s south façade. This entrance to Paris’s main transportation hub is captured via two very different methods. Pissarro’s work is an oil painting focusing on the energy of the crowd in the courtyard, and the other is a photograph, recording the building’s architecture with an almost archival sensibility. Although the Cour du Havre painting and the postcard of the Gare Saint-Lazare depict a shared location, they demonstrate different aspects of modernity, with the use of contrasting styles due to Pissarro’s ideological influences and the postcard’s commercial function.

The Gare Saint-Lazare, which opened in 1837, holds a place as the city’s first commercial train station (1). Its renovations and railways, added throughout the 19th century, was part of the capital’s industrialization that contributed to its population growth. According to the art historian Robert Herbert, about 40 percent of train riders in Paris went through Saint-Lazare, and most of those passengers came from the suburbs to work or to enjoy the city’s leisure activities. The train stations were the entrances to Paris, thus a point of access to commercial and entertainment districts (2). The city’s massive influx of visitors attests to the power of the railway industry to support commerce. As such, the Gare Saint-Lazare served as a grand introduction to modern life for many.

During the earlier decades of Haussmannization (c.1850-1870s) the Saint-Lazare station and its surrounding area were heavily renovated. The Rue d’Amsterdam and Rue Saint Lazare to the east and south were tightly packed with new apartment buildings. The station itself expanded several times to include the grand façade and the courtyard, Cour du Havre, in front of the east wing (3). Behind this entrance was the network of railroads that connected Paris to the suburbs and far reaches of France. The Gare Saint-Lazare was not only a transportation center; it was a gathering point, a place for reunions and farewells. With this activity, the train station and the people around it were rich subjects for artists like Pissarro who took an interest in modernity.

Pissarro, like many of his Impressionist friends, was fascinated with modern life. Whether that be rural field workers or city traffic, he thoroughly embraced the idea of modernity in both his subject and style. In Cour du Havre, Pissarro’s markings are loose and experimental with varying texture and thickness. Even within the painting, the artist’s technique changes. For instance, notice the carriage in the lower left corner compared to the one in the upper right. The latter appears much more hastily done, which could be an aspect of the high levels of activity that Pissarro was trying to convey. As Brettell and Joachim Pissarro describe, the artist was fascinated by the movement in cities, seeing it as an insight to the exchange of goods and labor (4). Pissarro’s variable technique was a means of illustrating the city’s incessant motion and commerce. In conveying the essence of the city, viewers can also spot details that would have been familiar to a late 19th century Parisian, such as the Morris column in the foreground, horse carriages, cafe tables (suggested by the white tablecloths), and possibly an omnibus along the left hand passageway. The indistinct nature of many of these objects can be attributed to Pissarro’s perception of modernity, with its bustling activity around the train station. The artist is capturing the Cour du Havre in all of its glory and modern chaos.

Pissarro’s loose, painterly touch is also a sign of his rejection of the academic style, promoted by the École de Beaux-Arts. Although other artists were also pushing back against the Academy, Pissarro’s stance was additionally fueled by his anarchist beliefs. According to the artist’s biographers Shikes and Harper, Pissarro was opposed to all kinds of centralized authority for the ways those institutions restricted personal freedom (5). Some theorists who Pissarro favored stated that “under anarchism the artist would be free to express his own concept of the beautiful” (6). Pissarro engaged in this anarchist artistic practice: “Most fundamental was his disregard for bourgeois standards of ‘beauty’… He consistently painted without regard for academic aesthetics, thus in a sense defying the state” (7). These aesthetic choices are seen in Pissarro’s abstraction of the Cour du Havre. Among many factors, his irregular brush strokes and busy composition most vividly contrast with academic style. Also, his choice to paint a crowd of city goers in front of the train station is, in itself, a decisive remark on what is beautiful and worthy of painting.

In an 1893 letter to his wife, Pissarro commented on the beauty of the area (8). Through Pissarro’s composition, we can see that his idea of beauty prioritizes the crowd over the city architecture. The figures of the crowd take up the majority of the painting, and as a whole they seem to congregate toward the upper left corner. When studying this painting at a distance, the crowd appears as an energetic mass of people, with their movements complemented by the rhythm of Pissarro’s colorful brushstrokes. This human gathering has a political significance, as their constantly moving energy suggests the potential for riots and uprisings. Pissarro made it clear in his writings that he believed France was on the brink of change. One year before he painted the Cour du Havre, Pissarro wrote to his son Lucien, “It is easy to see that a real revolution is about to break out—it threatens on every side. Ideas don’t stop!” (9). Pissarro was expecting a revolution, and his depiction of the crowd suggests that imagined potential for change.

Although the bodies can be viewed as a group, they are not a monotonous crowd. The figures show a vibrancy in color and rhythm. Their forms, distinguished by their clothing, are given in brief but very suggestive detail. Notice the variety in color and texture of the clothing worn by individuals in the lower left of the painting [Fig. 1a]. The way Pissarro paints figures, with varying brushstrokes and at a small distant scale, may not be with great clarity, but the forms on their own are still complex works.

Upon closer inspection, I become aware that these figures are individuals with their own relationships and conversations by the way that they gather in small clusters. In some instances these relationships can be further identified by the associations Pissarro makes with similar clothing. For instance, the yellow hair pieces worn by the women near the cafe tables suggest that they are friends or coworkers [Fig. 1a]. Other pairings like this are visible throughout the details of Pissarro’s scene. The people in Cour du Havre are not an anonymous or dull crowd, instead they are full of energy and unique relationships, much like the actual city Pissarro was viewing.

Richard Brettell and Joachim Pissarro summarize the artist’s approach to figures in political terms: “For Pissarro, the delicate balance between individual, social class and ‘crowd’ that he steadfastly maintained in his painting had its roots in the political theories of his friends and colleagues in the anarchist movement” (10). This influence is evidenced in a close study of Cour du Havre. The composition is framed prominently around the crowd. However, as Brettell and Pissarro note, the artist’s figures are individually examined, then represented on a canvas as a whole (11). One of the anarchist publications that Pissarro followed, Le Revolte, advocated for artists “to reveal the truth to the public, to represent reality, thus inevitably criticize the social order” (12). Here, Pissarro is revealing a “truth” as he sees it. The careful attention paid to both the crowd and the individual emphasize their power.

There is also an element of chaos in Pissarro’s work. The courtyard’s uneven ground and off center archways suggest a level of instability. In addition, the artist’s use of complementary colors, violet and yellow, and the rhythm created by the irregular, highly visible brushstrokes all throughout the courtyard contribute to the sense of disorder. This chaos in the crowd and composition can be understood in the context of Pissarro’s politics which valued radical change. The instability was a step toward the anarchist utopia that Pissarro dreamed of (13).

The painting is also striking for its peculiar viewing angle. The buildings, including the train station, are cropped out of the scene. Its location is only visually identifiable by the arches in the background that make up part of the station’s facade. Without a skyline or a full building to provide reference, the scene can feel disorienting and ungrounded to a viewer. In reality, this perspective comes from Pissarro painting from a high window in the Hotel Garnier across from the Gare Saint-Lazare (14). The artist left out any pictorial cues that would have helped to frame the painting in the context of the room where he created it, such as a curtain or windowsill. Thus, viewers have to actively work to orient themselves. Shikes and Harper acknowledge that these framing choices in Pissarro’s cityscapes make us highly aware that our view of the scene is limited (15). In many ways, this composition recalls a photographic point of view. The cropped, downward angle is a familiar arrangement for early photographers exploring the potentials of the medium.

At first glance the Cour du Havre does not seem to have a focal point, and that contributes to the previously discussed sense of disorder. However, in a photographic sense, this painting does have a focus. Notice how the figures in the painting shrink as they move up the courtyard and become increasingly blurred toward the right side of the canvas. The appearance of placing things in and out of focus is suggestive of the selective blur of photography.

Pissarro’s work, in fact, both draws from photography and also simultaneously challenges it. For instance, Pissarro’s abstraction of the courtyard demonstrates the conflict some Impressionist artists had with the increasingly popular medium. The interpretive nature of Pissarro’s scene shows a liberation from the confining modes of mechanized vision found in photography. In Baudelaire’s “Salon of 1859,” the art critic warns of how photography corrupts the artist’s imagination due to the new technology’s ability to essentially reproduce nature. In other words, Baudelaire feared that art was deteriorating when artists attempted to copy reality (16). Pissarro’s work seems to sympathize with this idea. His unique style pointedly demonstrates his freedom from imitative photography, and instead expresses the world in his own imaginative way.

Although we do not have as much information on the photograph of Saint-Lazare, we can see that it portrays the same side of the station as Pissarro’s painting, and that it was also taken from a hotel window given the height of the scene [Fig. 2]. However, this photograph shows the entirety of the facade and even some of the surrounding streets. In contrast to Pissarro’s piece, the straight, horizontal view and skyline provide an unambiguous nature to the photograph. With the postcard, the viewer’s attention goes first to the building itself, with all of the regularity created by the pattern of windows and architectural features. The orderly and symmetric elements of the building contribute to the image’s overall mechanical quality.

In addition, there are fewer people in the courtyard. By the nature of the black and white photograph, their individuality appears reduced. Also, their presence seems to revolve around the Gare Saint-Lazare. Notice how the people traversing the sidewalks appear to wrap themselves around the building [Fig. 2]. In fact, many other parts of the image also lead back to the station. The building on the left is shown at an angle, so its architecture points to Saint-Lazare, and the shadow cast by the buildings on the right does the same. Unlike in the painting, the Gare Saint-Lazare is clearly shown as the main feature of this work.

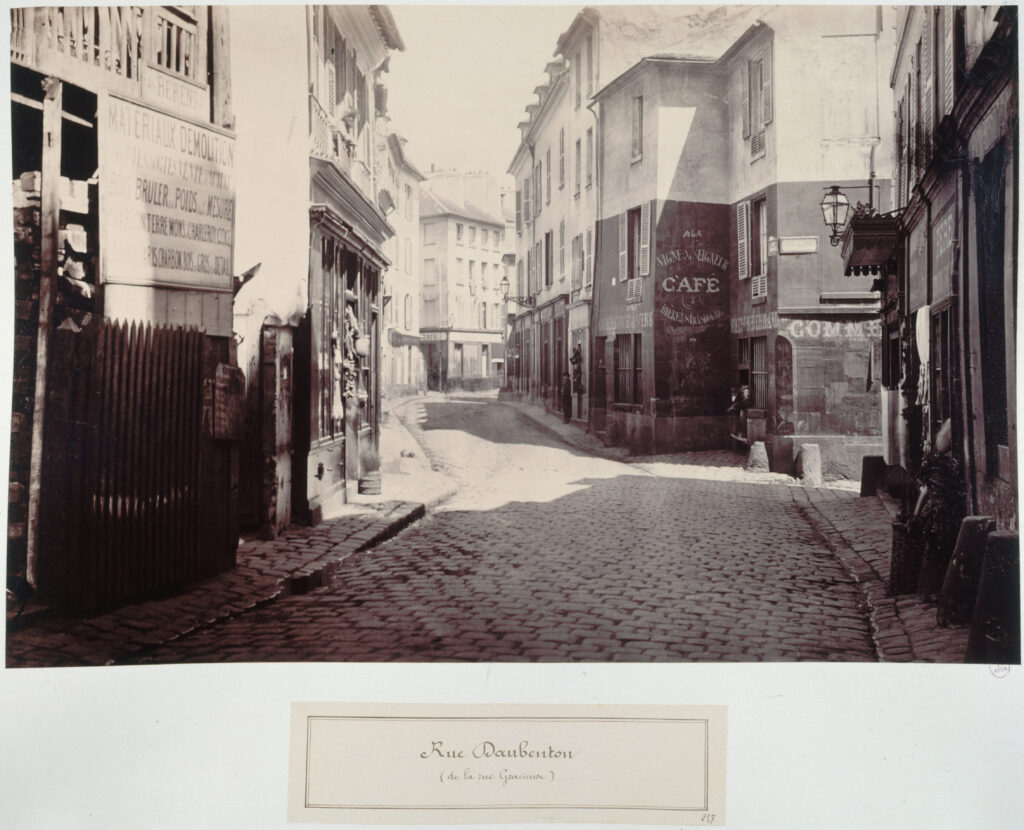

The straightforward depiction of the Gare Saint-Lazare suggests its purpose as documentation. This photograph was meant to record the train station and capture the building’s architectural details. The philosophy of using photography as a means of documentation was popular for capturing the new and old parts of the city. During the years of Haussmannization, many photographers took part in documenting Paris’s architecture, especially Charles Marville who was hired by the French government to document the city’s transformation. Marville commonly took photographs with views down streetways (17). The Saint-Lazare postcard uses this technique too. Notice the expansive view of the Rue d’Amsterdam on the right side of the station. Not only does the postcard capture Saint-Lazare’s new architecture, it displays the linear street plans conceived by Haussmann. The postcard follows Marville’s tradition of archiving a location. However, there is a slight difference between the way Marville immortalizes a location with the stillness and lack of people in his scenes [Fig. 3] versus the way the anonymous photographer freezes a moment in time using short exposure. This technique of the Saint-Lazare postcard was particularly good at capturing realistic detail; therefore the medium was very useful in recording the appearance of the city’s changing architecture.

One reason that people bought postcard images like this was to remember and share an experience. Around the turn of the century, there was a postcard mania. Billions of these illustrated cards were produced and distributed, especially in France. According to postcard collector, Leonard Lauder, the cards had such great public appeal because they showcased the excitement of the era (18). Sights of Paris’s new architecture was just one of the many forms that postcards took. Also, consider how many travelers arrived in Paris through the Gare Saint-Lazare. Visitors likely bought this image as a souvenir. The postcard’s function as a commodity of the tourist industry is a reminder of the growing population and thriving commercial culture in Paris. Since photography allowed for the mass production of identical images, this postcard was able to be purchased and shared among many individuals. The people who bought and sold it made up a network of mass distribution. Photographic postcards, like this, contributed to the visual mass culture of Paris.

The postcard image made its appeal by clearly depicting a recognizable landmark for its consumer audience. This commercial aspect of Paris was something that Pissarro reportedly despised (19). As an observer of both pieces, I’m curious if Pissarro’s views were in conflict with the consumer and tourist culture that the postcard represents. As a reminder, the railway industry, largely owned by banks, played a significant role in facilitating Paris’s commercial economy (20). Thus, the photograph of the Gare Saint-Lazare embodied the commercial nature of Paris in multiple ways. In one of Pissarro’s letters, the artist stated that he did not want to sell all of his Saint-Lazare artwork, that he wished to keep some for himself. Based on this painting’s provenance history, the Cour du Havre was one of the works that Pissarro had in his possession until he died (21). For one reason or another the artist favored this painting. Perhaps it was the modernity of the scene or painting’s expressive quality. Whichever reason, Cour du Havre illustrates Pissarro’s personal outlook on modern life which was highly influenced by his anarchism and individualism. Pissarro was able to use the medium of painting, in a way that was unique to him, to convey his ideology. On the other hand, the photographic postcard reproduces the actual details of Saint-Lazare in such a way that commodifies the new architecture of Paris. The different influences and functions of each of these works are revealed in their form. Though the painting and the postcard show the same physical location, their unique perspectives, detail, and focus highlight different aspects of modernity. Pissarro studies the nature of the crowd going about their daily life, and the photographer showcases an icon of modern Paris for a wide consumer audience. Demonstrated in Pissarro’s painting and the postcard are two different views of the world created by the unique perceptions of each artist, and their commercial goals.

(1) Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manet, Monet, and the Gare Saint-Lazare (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1998), 67.

(2) Robert Herbert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 196.

(3) Wilson-Bareau, Manet, Monet, 69-76.

(4) Richard Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, The Impressionist and the City: Pissarro’s Series Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), xxi.

(5) Ralph E. Shikes and Paula Harper, Pissarro, His Life and Work (New York: Horizon Press, 1980) 68, 228.

(6) Ibid, 226.

(7) Ibid, 239.

(8) Camille Pissarro, Letters to His Son Lucien, ed. John Rewald, trans. Abel Lionel (New York: Pantheon, 1943), 207, http://archive.org/details/lettersto00piss.

(9) Pissarro, Letters, 195-196.

(10) Brettell and Pissarro, The Impressionist and the City, xxiv.

(11) Ibid, xxii.

(12) Shikes and Harper, Pissarro, 219.

(13) Ibid, 230.

(14) Brettell and Pissarro, The Impressionist and the City, 51.

(15) Shikes and Harper, Pissarro, 303.

(16) Charles Baudelaire, “The Salon of 1846: On the Heroism of Modern Life,” reprinted in Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology, eds. Francis Frascina and Charles Harrison (New York: Harper and Row, 1982), 19-21.

(17) Shelley Rice, Parisian Views (Cambridge & London: MIT Press, 1997), 85-88.

(18) Lynda Klich and Benjamin Weiss, The Postcard Age (Boston: MFA Publications, 2012), 12-13.

(19) Brettell and Pissarro, The Impressionist and the City, xxxi.

(20) Shikes and Harper, Pissarro, 234.

(21) “Camille Pissarro (1830-1903),” Christie’s, accessed April 21, 2021, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5100006.