Emi Cormier (Class of 2020) analyzes the racial politics of Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs of the 1937 Ohio River Flood.

This essay was written for Professor McBreen’s Fall 2019 course Introduction to Photography.

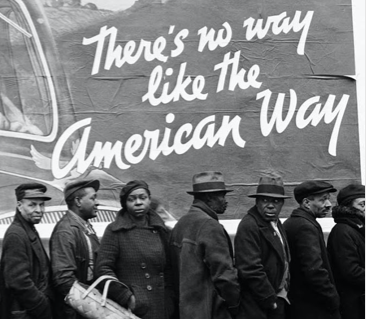

The Great Depression plagued the United States for much of the 1930s, but it was not the decade’s only tragedy. In 1937, Ohio and its surrounding states suffered a horrendous flood, which left over 400 people dead and more than one million homeless (1). One of the most heavily impacted cities was Louisville, Kentucky, where three-fourths of the city was inundated (2). Margaret Bourke-White, a well-respected photographer for LIFE Magazine —the leading American magazine for much of the twentieth century—covered the flood in a spread for the magazine’s February 15, 1937 issue (3). Her primary photograph, “At the Time of the Louisville Flood” [Fig. 1]—the largest in the spread—eventually became an iconic, widely reproduced image from the Depression era.

Captioned in the magazine with “The Flood Leaves its Victims on the Breadline,” it is a strikingly powerful image. It depicts African-Americans waiting in a line outside a relief agency. With the exception of three or four unfazed people, who return the camera’s gaze, most people appear seemingly unaware that their photograph is being taken. Their stoicism reads in stark contrast to the massive propaganda directly above them. [Fig. 2]. With bold letters reading “World’s Highest Standard of Living” and “There’s no way like the American Way,” the billboard depicts what was then—and arguably now for some—the American ideal of the nuclear (and white) family: a father, mother, and two kids, complete with a dog hanging out of their car window as they drive off freely into the distance. In this context, the upbeat patriotism of the phrase “There’s no way like the American Way” has a controlling, callous tone to it, alluding to the idea that the white capitalist standard of living in America is the only way to live correctly, in sharp contrast to the experiences of the people, going nowhere, in the line beneath it.

The Life article briefly touches on the billboard, referring to it as “part of a propaganda campaign of the National Association of Manufacturers” (4). The Hagley Museum’s website elaborates on this, featuring an article on the National Association of Manufacturers’ mission during the Depression: the NAM sought to delegitimize both President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and labor unions. Through its main agency, the National Industrial Information Council (NIIC), NAM was able to create and publicize an array of propaganda, including but not limited to “2 million copies of cartoons, 4.5 million copies of newspaper columns written by pro-business economists… [and] 45,000 billboards on highways and in major cities, seen by an estimated 65 million Americans daily” (5). With this, NAM promoted the successes of capitalism during one of the bleakest economic periods of U.S. history; its campaign also celebrated intensely nationalistic ideals when the “American Way” was so out of reach for many of its citizens.

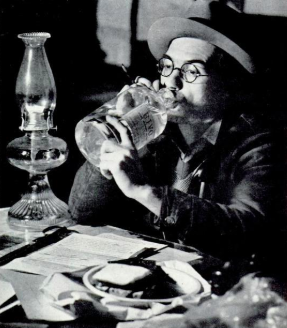

The Life text describes African-Americans with condescension, painting them as helpless, and in a way, complacent victims. This can be seen in lines such as “people came with baskets, bags, pails, or merely empty hands and hungry stomachs” (6). This narrative of people waiting in the line is made more patronizing considering how much the three-page spread dedicates to the hardworking newspaper staff of the Louisville Courrier-Journal. Those images—making up an entire page—present the reader with white newspaper editors and writers working tirelessly by lamplight [Fig. 3], as well as drinking boiled water [Fig. 4], “the only safe water for drinking in the flooded city” (7). This narrative is in stark contrast to the previous pages, particularly the initial photograph, as it promotes the newspaper workers as making an active effort to persevere through hardships.

The third page in the spread contains an image of church pews filled with canned foods [Fig. 5] and two other images of African-Americans, including one that captures a sleeping woman and families taking refuge in a relief station [Fig. 6]. Both of these images, along with their accompanying texts, further perpetuate the idea that African-Americans were unable to recover from the circumstances brought on by the flood, while the newspaper editors—also facing the harsh effects—remained dedicated to their work, even if it meant sleeping in the office.

Just as revealing about the politics of this story are the other photos Bourke-White took in Louisville that weren’t chosen for Life. Bourke-White also captured a heartbreaking image of a homeless African-American man [Fig. 7], but that photograph wasn’t included in Life (8). Perhaps the reason Life editors chose not to include the photograph of the homeless man is that it was too raw, and too personal. “At the Time of the Louisville Flood” contains a narrative, an agenda that the rest of the spread can follow, which this man does not support. Additionally, “At the Time of the Louisville Flood” had the potential to resonate with a larger audience than just those affected by the flooding in Louisville. The billboard in the background paired with the people in the breadline was symbolic of the intense gap between poverty and wealth many readers were faced with in their daily lives during the Depression.

Another photograph that didn’t make it into the magazine spread is an untitled image extremely similar to “At the Time of the Louisville Flood.” This image, however, was taken by Bourke-White from a slightly different angle, and therefore doesn’t present the same message [Fig. 8]. In the second image, more people are looking into the camera, and more notably, have more expressive faces when doing so. Additionally, the billboard promoting the American Way is no longer the focal point of the photograph; instead, the viewer is inclined to draw their eyes down the line of people standing in the breadline. In doing so, one can potentially write their own narrative for each person in the line: from the three men glancing slyly into the lens while leaning against a display to the man about two-thirds of the way back posing as if he’s taking a swig from what appears to be a liquor bottle. This image is more animated, capturing the subjects in the photograph with more individual, active agency to express themselves.

By contrast, what we see in “At the Time of the Louisville Flood” is a group of people who function more as symbols, as foils to the billboard above them. Their individual identities have been subsumed to the larger point about racial injustice. The stunning irony of the cult-like message that claim there is no way of living that can compare to the “American Way’ is its primary message. It’s likely the editors of LIFE chose this image to be the most prominent in the spread because it supports a narrative that the Louisville community had not only been devastated by the Ohio flood, but by the Great Depression as a whole (9).

Bourke-White’s photograph potentially elicits feelings of relatability for those suffering economic hardships, then and now. There is something extremely powerful about an image that sustains impact for decades after its original publication. The reason this photo has the notoriety it does, and continues to be reprinted at the frequency that it has, is due to the fact that anyone who has experienced economic hardships can look at the image and identify with it. It is nearly impossible to look at the billboard and miss the point about the blind disregard of nationalism, and which citizens have been left out of the American dream. Even when photographs are originally made as journalistic documents, Bourke-White’s reminds us of the lasting, and still relevant, social meanings that images can have.

(1) “Ohio River Flood of 1937.” Ohio River Flood of 1937 – Ohio History Central. Accessed December 1, 2019. http://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Ohio_River_Flood_of_1937.

(2) “LIFE.” Google Books. Google. Accessed November 1, 2019.

https://books.google.com/books?id=WFEEAAAAMBAJ&ppis=_e&lpg=PA11&dq=louisville&pg=PA11#v=onepa

ge&q=louisville&f=true.

(3) ibid.

(4) ibid.

(5) David Gray, “The National Association of Manufacturers and Visual Propaganda.” Hagley Museum and Library Website, September 22, 2014.

https://www.hagley.org/librarynews/research-national-association-manufacturers-and-visual-propaganda.

(6) “LIFE.” Google Books. Google. Accessed November 1, 2019.

https://books.google.com/books?id=WFEEAAAAMBAJ&ppis=_e&lpg=PA11&dq=louisville&pg=PA11#v=onepa

ge&q=louisville&f=true.

(7) ibid.

(8) Ben Cosgrove, “’The American Way:’ Photos From the Great Ohio River Flood of 1937.” Time, May 28, 2015. https://time.com/3879426/the-american-way-photos-from-the-great-ohio-river-flood-of-1937/.

(9) “LIFE.” Google Books. Google. Accessed November 1, 2019.

https://books.google.com/books?id=WFEEAAAAMBAJ&ppis=_e&lpg=PA11&dq=louisville&pg=PA11#v=onepa

ge&q=louisville&f=true.