A rare anti-slavery medallion illuminates the complex relationships between the 19th-century abolitionist movement and the struggle for women’s rights.

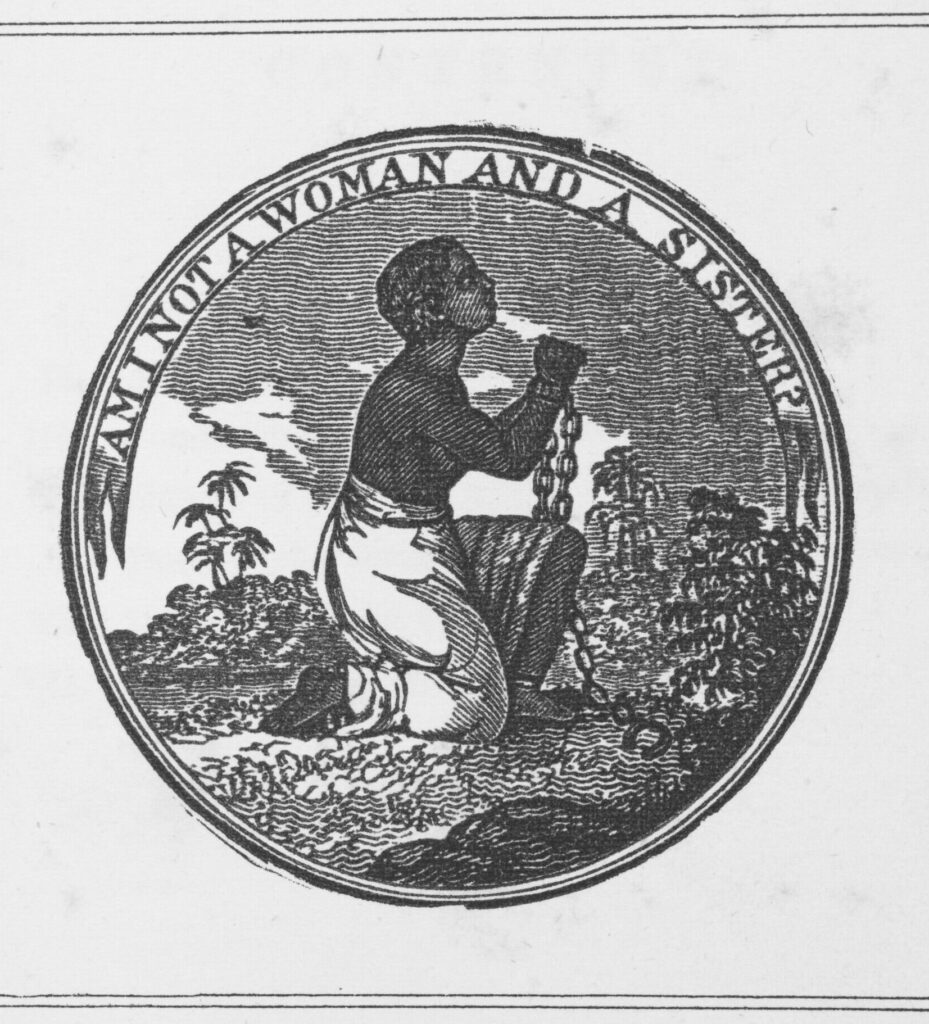

A small but impactful copper coin recently arrived in the Wheaton College Permanent Collection. It’s the latest addition to a growing cache of materials that will give students more opportunities to explore African American history with original objects. The coin features a kneeling enslaved woman looking upward, with a manacle falling from the wrist of her raised arm. She is surrounded by the text, “AM I NOT A WOMAN & A SISTER / 1838” [Fig. 1]. On the reverse side “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA” appears on its outer edge, with “LIBERTY / 1838” inside a crown of laurel leaves [Fig. 2]. It is currently part of the 2022 Limits of Visibility exhibition, curated by History of Art senior majors and on view in Watson Fine Arts.

Gibbs, Gardner, and Company, Belleville, NJ

After a design by an unidentified American artist

Anti-Slavery Medal, 1838

Copper, 1.12 x 1.12 x .06 inches (2.84 x 2.48 x 0.18 cm)

Purchased with the Kenneth C. and Louise McKeon Deemer ‘33 Fund

Since canonical histories have often abbreviated or forgotten altogether the lives and contributions of Black women, the coin is an especially valuable resource for future courses and research in African American art, history, race and representation, and Women’s and Gender Studies. History of Art Professor R. Tripp Evans first discovered it at the Humane: Objects of Kindness and Cruelty exhibition curated by Adam Irish at his Providence, Rhode Island gallery. In the following interview, Emily Gray (Class of 2022) discusses the meaning and context of the anti-slavery medal with Professor Evans.

Gray: Thanks so much for talking with me today about this exciting new acquisition. The date on the coin, 1838, indicates it was created 23 years before the start of the American Civil War in 1861. Can you tell us more about its historical context and purpose?

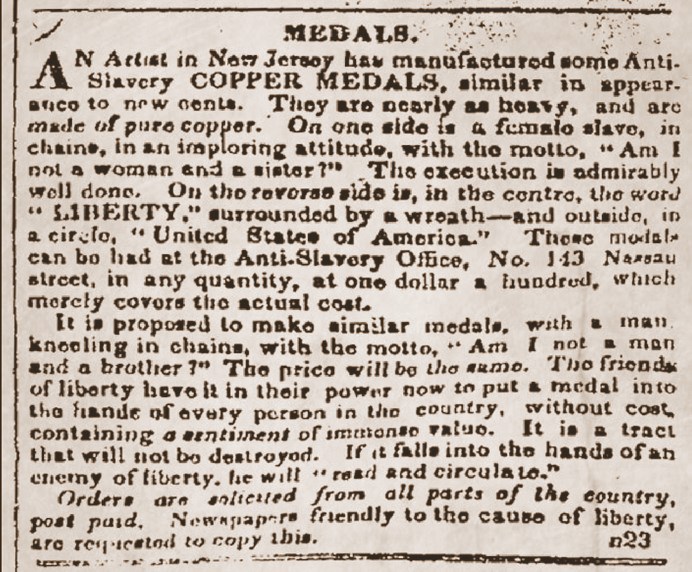

Evans: Happy to discuss the work, Emily. This coin was intended to broadcast an anti-slavery message to the U.S. population at large. A contemporary advertisement identifies the medal’s creator as simply “an Artist from New Jersey,” but the image is based on an engraving from George Bourne’s 1837 Slavery Illustrated in Its Effects Upon Women and Domestic Society. [Fig. 3] The engraving in Bourne’s book, in turn, derived from William Hackwood’s 1787 anti-slavery medal for Wedgwood, the British ceramics company. [Fig. 4] But the Wedgwood design featured a kneeling enslaved man paired with the phrase, “AM I NOT A MAN & A BROTHER?” Wheaton’s medal was actually an active form of currency. Its very use as a circulating coin was central to its protest function. After the Financial Panic of 1837, currency shortages led individuals and businesses to strike their own copper coins; given the inherent value of the material, these homemade coins (known as “Hard Luck Tokens” by collectors) qualified as valid currency. In their 1838 advertisement for the medal, its manufacturers explain that, because it would circulate as currency, the work represented “a tract that cannot be destroyed.” [Fig. 5] Even those who supported slavery would have been compelled to accept these coins, and thereby “read and circulate” their anti-slavery message.

Gray: What is the significance of the figure on the medallion? Is it common to see a woman on a coin like this? How does she (as an individual and/or as a symbol) relate to the abolitionist cause?

Evans: The substitution of an enslaved woman for the more common iconography of an enslaved man, as derived from Hackwood’s 1787 original, is significant and rare. The firm that produced the image advertised its subsequent plans to produce a coin featuring the more familiar image of a kneeling man, but it’s unclear if these were ever struck (it is worth noting that they chose to produce the more unusual iconography first). In either case, the male or female figure would have been intended as a universal representation of an enslaved person, rather than a portrait of any specific individual. Because Bourne’s 1837 text focused exclusively on the effects of slavery on women, his engraver introduced the female figure later rendered on this medal. This shift not only emphasized the particular evils of slavery as it applied to women, but it also suggested (as Bourne’s book did) parallels between the anti-slavery movement and early struggles for women’s rights more generally. There was considerable overlap between these advocacy groups in the 1830s, as seen in the work of women like Sarah and Angelina Grimke, who used the anti-slavery cause to address their own plight as women. This connection between abolitionism and women’s rights was controversial at the time and threatened to splinter anti-slavery groups.

Gray: The message on the edge (“AM I NOT A WOMAN & A SISTER”) seems charged with emotion. If she is not a woman or a sister, who is she? Was this powerful message a common one in antebellum America?

Evans: The text that surrounds this coin derives from Hackwood’s more widely circulated text, “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?”— a pointed confirmation of the humanity of its subject, and a challenge to white audiences to acknowledge their common bond with enslaved people. The forthrightness of this appeal—later echoed in Sojourner Truth’s famous 1851 speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?”—is tempered by the supplicant posture of the chained figure (whether male or female), a pose that has led some contemporary viewers to find this imagery, however well intended, to be paternalistic or even humiliating. To cite a recent example of this attitude, Boston’s 1876 Emancipation Monument— which depicts Abraham Lincoln standing over the crouching figure of a formerly enslaved man—was removed in 2020 for its suggestion of African American subservience. The substitution of a woman for Hackwood’s original subject also complicates its reception, given the period’s general assumption of female subservience. We see this even in Edmonia Lewis’s tribute to Emancipation, Forever Free (1867), in which this African-American sculptor posed her emancipated male figure standing erect while depicting his female companion kneeling.

Gray: What were the attitudes of white abolitionists toward Black women’s rights in the 19th century? Would they have supported this message?

Evans: Neither white nor Black abolitionists were monolithic in their attitudes about women’s rights. Anti-slavery activists like Frederick Douglass (who escaped slavery the year this coin was struck) was an early supporter of women’s rights, regardless of race. The Grimke sisters, noted above, were part of a vocal contingent of abolitionists who paired anti-slavery and women’s rights messaging—often facing strident opposition by fellow abolitionists. Following Emancipation, similar tensions arose among former abolitionist activists about the urgency of extending suffrage to women (including Black women), in light of the struggle to win the vote for Black men. Most visibly, Frederick Douglass and his friend Susan B. Anthony split over this issue.

Gray: Why did you propose this artifact for Wheaton’s Permanent Collection? What courses would you include it in? And what do you think is its relevance for today?

Evans: I was determined that Wheaton acquire this work for its Permanent Collection given the rarity of its iconography and the rich opportunities it presents for students to address issues of race, gender, representation, equity, and political activism. I will use this medal in my introductory classes, “American Art and Design” and “African American Art and Design,” and plan to study it in greater detail when I teach my upper-level seminar, “Slavery, Protest, and the Public Monument.” Because so little is known about the specific historical context of this medal, the work will provide a great research opportunity for students in these classes. As an art historian, I am not only interested in the period that produced this image, but also in the ways contemporary African American artists have reclaimed and revised such historic imagery. Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker, for example, have both successfully (and often controversially) enlisted 19th-century images of enslaved people in their work as a commentary on contemporary racial politics. I would hope that students today find tremendous value in this medal, whether their interests lie in history, art history, politics, political science, or gender studies. It is a difficult piece, but in its difficulties lie real opportunities for productive work.

Professor R. Tripp Evans graduated from the University of Virginia with a B.A. in Architectural History. He received his PhD in the History of Art at Yale University. He has been a guest lecturer at Yale, Wellesley College, and Brown University. He has written two books: Romancing the Maya: Mexican Antiquity in the American Imagination, 1820-1915 (2004) and Grant Wood: A Life (2010). Currently, Professor Evans’s scholarly work analyzes the role of the American house museum through historical New England homes. He is also deeply involved in the arts and humanities in his home city of Providence, Rhode Island, where he has served as President of the Board of Directors for the Providence Athenaeum and on the Rhode Island State Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission.