Calais Mustoe (Class of 2021) examines the sexual politics of looking in Mary Cassatt’s Antoinette at Her Dressing Table (1909)

This essay was written for Professor McBreen’s class Modernism and Mass Culture (Fall 2019). The research assignment was to locate, and then critically compare a modernist work of art with a related object of mass culture.

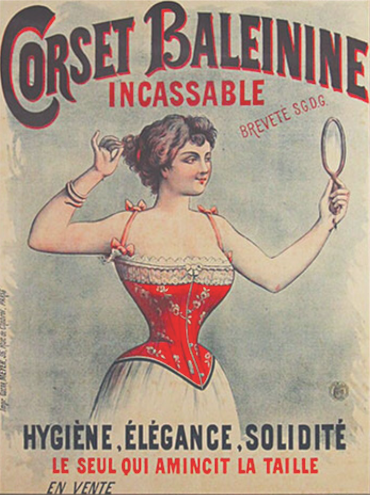

Mary Cassatt’s Antoinette at Her Dressing Table from 1909 shows a young woman sitting at her vanity and gazing at herself in a handheld mirror [Figure 1]. Her body is turned toward the viewer and her gown is partially undone as she leans her elbow on the edge of the table, contemplating her reflection. This painting is visually similar to a poster from nine years prior, possibly by Alfred Choubrac, for a French company selling whalebone corsets (1). The figure in the Baleinine corset advertisement [Figure 2] is also holding a mirror and in a state of undress, though vastly more revealing than in Antoinette. The vivid red corset cinches her middle, drawing the viewer’s eye to the product being sold. Her exaggeratedly tiny waist is the focus of the ad, and while the viewer is being sold the idea of the corset we are simultaneously being sold the image of the woman in the corset. She is on display, selling this product by selling the image of herself, as commodified as the actual corset.

Despite the parallel narratives, the woman in Cassatt’s Antoinette at Her Dressing Table is not on display in the same way. Cassatt does not posit the woman an object of public pleasure or as a commodity, nor does it cater to the male gaze as much as the Baleinine advertisement and is therefore more sympathetic to the ways in which women were subject to visual observation in early twentieth-century France.

There is no reflection in the mirror that the corseted woman holds in the Baleinine corset ad. She isn’t looking at herself; she can’t be. Whereas in Cassatt’s painting, the reflection in the mirror behind the woman leads us to believe there will be a visible image in the handheld mirror and that she is actually seeing herself. This difference is key, for when viewing the corset ad, we are meant to imagine ourselves as her; we are (or could be, with their product) her reflection. She exists more for the observer than for herself. As John Berger describes in Ways of Seeing, this is the typical relationship between female consumer and advertisement: “[The spectator-buyer] is meant to imagine herself transformed by the product into an object of envy for others.”(2) The aim of the Baleinine ad is to promote business, and so the emphasis is on the viewer looking at her which functions through the mirror to “make the woman connive in treating herself as, first and foremost, a sight.”(3)

The Baleinine ad is reminiscent of other modes of female commodification at the turn of the century. Department stores, such as Le Bon Marché, were a new venue for putting women on display. Presentation became of central importance in a way that hadn’t previously been the case in small specialized shops.(4) As Theresa McBride, in her study of women’s employment in Parisian department stores, writes:

A significant part of the department stores’ merchandising revolution was the presentation. Expositions in the spacious galleries of the store, large display windows, publicity through catalogs and newspaper advertising shaped illusions and stimulated the public’s desires for the items offered. The salesperson was herself part of that presentation, helping to create an atmosphere of service and contributing to the seductiveness of the merchandise.(5)

The corseted woman in the Baleinine advertisement evokes a fin de siècle salesgirl. The way she’s represented can be seen as a reference to the tantalizing sexuality with which the department store salesgirl was associated. She’s also similar in the way she presents the product. She’s on display, representing the overall company in the same way as an employee represented Le Bon Marché, showcasing what the viewer might look like in the same way salesgirl often wore the clothes being sold in the stores. The woman from the Baleinine poster is part of the product; she’s a commodity. Unbreakable. Solid. These are some of the words used in the advertisement, and they can be attributed to the woman herself. Her pose is rigid, and with her pale skin and molded figure, she looks more like a statue than a woman—“half-human and half-merchandise” like the mannequins in Emile Zola’s novel, Au Bonheur des Dames.(11)

According to Kathleen Paton, Mary Cassatt had an interest in consumerism. Paton describes how Cassatt was “keenly interested in the upscale fashions of her day, both as a consumer and chronicler—and she often focused on clothing in her work.”(12) Paton also mentions one of Cassatt’s drawings from 1891: The Bonnet [figure 3]. The way the woman holds the strings of the bonnet together under her chin, to check her appearance in the mirror, suggests she is shopping, probably in a department store. But unlike the salesgirl or the Baleinine ad, she’s not modeling the clothes for an external audience; she’s doing it for herself. As in Antoinette, the handheld mirror is angled toward the woman and away from the viewer. By doing this, Cassatt posits both this and the woman in Antoinette as owners of their reflection. Though she may be imagining herself performing for a patriarchal society, the sitting woman in The Bonnet is not performing for the male gaze.

Berthe Morisot’s Psyche is also visually reminiscent of Cassatt’s 1909 painting [figure 4]. Painted decades earlier than Antoinette, Morisot exhibited Psyche at the 1877 Impressionist exhibition. About Morisot’s painting, Griselda Pollock describes how the view into the bedroom of the girl examining her full-length reflection in the standing mirror has “voyeuristic potential,” but importantly “at the same time, the pictured woman is not offered for sight so much as caught contemplating herself in a mirror in a way which separates the woman as subject […] from the woman as object.”(13) Pollock argues that Morisot allows the woman in her painting to be the subject and not just the object, not just “the surveyed female.”(14)

A similar analysis can be applied to Cassatt’s painting. There may be a voyeuristic potential to Antoinette given the private interior setting, and it might arguably perpetuate the association of women with vanity by use of the mirror, but the woman is not merely an object, and certainly not an object of pleasure the way that mass culture dictated. The woman in Cassatt’s Antoinette at Her Dressing Table is the holder of her gaze and the one returning it. Despite the visual similarities between the two pieces, the painting doesn’t rely on us as the viewer to shape her or define her. Although on display, the woman in Antoinette is the agent of her own activity.

1) Choubrac is credited for a similar advertisement for Baleinine Corsets. Given the fact that he was still alive in 1900, it’s very possible that he created this ad as well, although there’s no definitive indication.

2) John Berger, “7,” in Ways of Seeing (London, England, British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 1973), p. 134.

3) John Berger, “3,” in Ways of Seeing (London, England: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguins Books, 1973), p. 51.

4) Jon Stratton, The Desirable Body: Cultural Fetishism and the Erotics of Consumption (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), p. 28. Stratton argues that this emphasis on presentation can also been seen in the evolution of Expositions in the 19th century, that instead of teaching about machinery and science, “expositions came increasingly to display commodities” and appeal to tourists.

5) Theresa M. McBride, “A Woman’s World: Department Stores and the Evolution of Women’s Employment, 1870-1920,” French Historical Studies 10, no. 4 (Duke University, 1978): p. 665; emphasis mine.

6) Michael B. Miller, The Bon Marche: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store, 1869-1920 (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981), p. 80.

7) Ibid., p. 167.

8) Christine Poggi, “Mallarmé, Picasso and the Newspaper as Commodity,” Yale Journal of Criticism 1:1 (Fall 1987): p.140.

9) Ibid., p. 140.

10) Theresa M. McBride, “A Woman’s World: Department Stores and the Evolution of Women’s Employment, 1870-1920,” p. 679.

11) Rosalind H. Williams, Dream Worlds: Mass Consumption in Late Nineteenth-Century France,(Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982), 2. From Emile Zola’s novel, the main character arrives in Paris and encounters a department store: “Before them pirouetted three elegant mannequins […]. The heads of the mannequins had been removed and been replaced by large price tags. On either side of the display, mirrors endlessly multiped the images of these strange and seductive creatures, half-human and half-merchandise.”

12) Kathleen Paton. “Mary Cassatt at The Met,” The Met Store Magazine, 22 May 2018, https://www.metstoreblog.org/mary-cassatt-at-the-met/.

13) Griselda Pollock, “Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity” in Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art (London: Routledge, 1988), p. 81.

14) John Berger, “3,” in Ways of Seeing, p. 47.