Marley Reedy (Class of 2024) explores how artists in the current Limits of Visibility exhibition evoke the empowerment of being seen.

How many of us know what it is like to go unseen, and to be forgotten by history? Have we taken for granted the empowerment and ethics of visibility? Limits of Visibility is a Watson Fine Art exhibition curated by Wheaton College History of Art majors Olivia Doherty (‘22), Emily Gray (‘22), Whitney O’Reardon (‘22), and Sofia Vafiadis (‘23). It explores the political dynamics of representation through a juxtaposition of historical and contemporary representations of and by BIPOC people. Featuring works from the Wheaton Collection Permanent Collection and Gebbie Archives and Special Collections, the project encourages visitors to consider how identity, racism, and colonial violence are represented in print, photography, collage, sculpture, and other media.

Visitors may be moved to ask of these diverse works of art: who is being represented here, and who is not? What else is there to see and understand beyond the frame? How do these artists expand the power of agency to create one’s own visual story, while also acknowledging the limits in experiencing the lives or traumas of others? Those central questions animate the exhibition’s four thematic sections: From Stock to Self: Race and Representation; The Color of Race: Myths and Markers; Queering the Classical, and Visualizing What Can’t Be Seen. I was particularly interested in the central theme of visibility. The artists selected speak to a range of how the visible can be manipulated, in transforming the potential relationships between subject and viewer. The choice to allow or withhold visibility demonstrates the power of what cannot be seen as much as what can. As I visited and revisited this exhibition in Watson, I was encouraged to rethink my assumptions about the representation of identity and activism through art.

South African artist Sue Williamson’s series A Few South Africans (1983-84) depicts female activists of the anti-apartheid movement, Mamphela Ramphele, Albertina Sisulu, and Amina Cachilia. They each fought against the dehumanizing violence of a racist regime oppressing the 80% non-European population of their country. [Figure 1]. These eye-catching photographic etchings invite viewers into the life story and accomplishments of each heroic woman, who battled to end Afrikaner white rule through non-violent tactics. In an accompanying audio interview recorded for the exhibition by Vafiadis, Williamson recalls that most people in South Africa in the 1980s would not have even recognized the faces of these prominent activists, because of repression and state censure (1). Her goal was to support these women by circulating images of them, and did so by making postcards of her prints. Symbolic details relating to the activist work of Ramphele, Sisula, and Cachilia hover over vibrant South African design patterns. In the print of Albertina Sisulu, for example, Williamson recalls her arrest via a group of police officers as well as her role as one of the founding members of the United Democratic Front with a banner reading “UDF” (2). In that way, Sisulu’s political work and not just her likeness becomes a central focus of this piece. As with all of the prints in Williamson’s now iconic series, it reveals the intimate attention and reverence the artist pays to the social acts of the women. The work is an evocation of visibility, grounded in genuine care and respect. A Few South Africans literally and metaphorically center their female subjects by making their stories known– for now and for history.

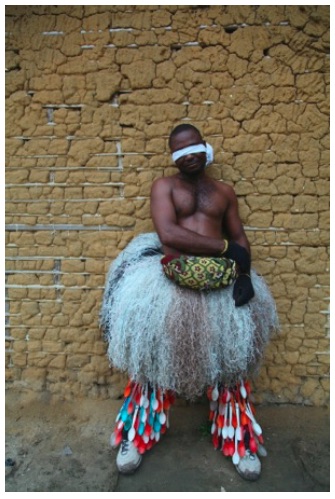

Zina Saro-Wiwa, a British-Nigerian artist, challenges the limits of visibility in two powerful large-scale photographs Men of the Ogele and Soul of a Nobody [Figure 2, and cover image above], a pair of works opening the final section of the exhibition curated by Gray: Visualizing What Can’t Be Seen. In this section contemporary artists, all from the Global South (Nigeria, South Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Mexico) visualize the limitations of representation in conveying the dehumanizing impacts of colonialism, apartheid, police brutality, and drug violence. In their own ways, these artists each deny the “consumptive gaze of the viewer-voyeur” inherent to photography (3). That theme is introduced by Saro-Wiwa’s pair of images by the fact of both faces being hidden from the viewer; the Ogele man wears a blindfold, while the figure in Soul of a Nobody faces away from the camera. While we cannot see their face, the pink dress may be a marker of identity; a clue tempting us to fill in the gap. An unconscious urge to “know in totality” may push us to assume this subject’s gender, but Zina Saro-Wiwa’s framing calls out this inherent urge to categorize people. (4) As we jump to conclusions about the subjects’ identities, we are also asked to question the basis of those assumptions. The figure displays an awareness that they are being observed, through a slight turn towards the left shoulder, but in the end, their personhood is withheld from the viewer. Is there freedom granted by limiting what is visible? Are photographic subjects ever truly protected from the assumptions of their viewers? In the History of Art capstone senior seminar connected to this exhibition with Professor Ellen McBreen, Gray and other student curators read the work of the postcolonial thinker Edouard Glissant, who proposes a “right to opacity.” Glissant questions whether it is truly possible, or ethical, to be legible across cultural divides. In some ways, without having a face to assign to the subject, perhaps the unnamed people in Saro-Wiwa’s photographs have the upper hand on the viewer. They may seem aware of our gaze but their gaze is withheld from us. In that way, Saro-Wiwa empowers them to keep a more profound part of their identity for themselves.

The Congolese artist Sammy Baloji extends these ethical questions in his Untitled 8 from the Mémoire (2006) series of photographic collages [Figure 4]. The black and white historical photographs he uses depict enslaved African laborers, forced to work for the Union Miniére du Haut-Katanga mining company, supported by the brutal Belgian colonialist regime (4). Baloji’s work is based on research, and he located these horrific images in the company’s archives. He then placed the men from the photograph against a more recent color image of his hometown, Lubumbashi, a city in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In that way, Baloji brings the past in a direct conversation with the present. As Gray’s accompanying wall text points out: “a uniformed man awkwardly stands to the right of the slag pit, acting as an overseer, in a hierarchy of human abuse for profit.” By re-appearing in the present day, the persistent memory of this abuse denies the historical erasure of endured colonial violence. Since the men’s gazes are powerfully directed at the camera, viewers are unable to ignore their undeniable presence in the contemporary landscape, still a part of the earth in which they labored. Balojij makes visible a history central to the current realities of the DRC, which, although unseen in the lived present, cannot be buried.

Baloji makes a telling contrast to another work installed nearby, Romare Bearden’s In the Garden (1979) which concludes O’Reardon’s section The Color of Race: Myths and Markers [Figure 5]. The woman depicted in this color lithograph stands amongst the flora and foliage of her garden with her harvest tucked in one arm. She is shown as powerfully connected to the land, through both her bare feet and the careful hands which cultivated her earth. The work was inspired by Bearden’s American Southern roots and African American ancestors. The collage-like process he used to make In the Garden frees the subject from the confines of an existence in reality, expanding the potential to embody more than just one woman in a garden. She also conveys the reclamation of land, growth, food, and the autonomy historically denied to African American people. Bearden portrays the rich history of food as a form of resistance for African Americans, and a tool of Black self-determination. This figure is free to evoke all of these things. By abstracting from what is immediately visible, Bearden empowers his subject as an ideal of a Black female, a beautiful and joyous representation of life and independence.

Collectively, these artists empower the subjects of their works, as people who symbolically evoke structural oppression, and the endurance of its lasting impacts. In order to expand the conversation, the curators interviewed other participating artists (Kevin McCoy and Miguel A. Aragón) as well as members of the Wheaton community: (Emmanuel Leal, Class of 2023; Faith Freeman, Class of 2022; Shaya Gregory Poku, former Associate Vice President for Institutional Equity and Belonging; Desnee Stevens, Associate Director, International Student Services; Joe Wilson, Jr., Professor of the Practice of Theater, and Artist in Residence, Theatre and Dance; and Sarah Estrela Beck, Class of 2015, and Curatorial Fellow, Art Institute of Chicago). Their personal insights are accessible via the wall panels, and suggest how many different ideas the works on display can potentially inspire. In that way, the artists chosen for Limits of Visibility represent the empowerment of being seen but also the potentials for being understood that exist in the process of trying to understand. They represent the lives of real people whose stories deserve to be made visible.

Footnotes

(1) Sofia Vafiadis, Audio interview with Sue Williamson, 5/26/2022 on ARTstor

(2) Sofia Vafiadis, Audio interview with Sue Williamson about Albertina Sisulu, 5/26/2022 on ARTstor

(3) Emily Gray, section summary wall text for Visualizing What Can’t Be Seen

(4) Emily Gray, wall text for Zina Saro-Wiwa Soul of a Nobody

(5) Emily Gray, wall text for Sammy Baloji Untitled 8 from the Mémoire Series