Adi Shmerling (Class of 2022) proposes an exhibition idea: art made in Mozambique and Tanzania that tells the story of socialist activism in eastern Africa.

This exhibition proposal was completed for Professor Ellen McBreen’s Fall 2018 class The Art of Writing About Art.

The fundamental purpose of this exhibition would be to use Mozambican and Tanzanian artwork, produced from 1950 to 1970, to contextualize and further examine the rise of socialism in eastern Africa. Furthermore, the exhibition would take a close look at the Mozambican war of independence from Portugal that may have been directly affected by this rise in socialist thought.

The exhibition would be split into three galleries, each with its own distinct theme and artistic medium to focus on. The first gallery would house a number of propaganda posters produced during and after the war of independence to provide historical narrative context, showing the audience what was happening in Mozambique at the time, what citizens were feeling, and how propaganda was able to tap into these emotions to push a political agenda. Gallery Two would focus on the oil paintings of Valente Malangatana, a prolific Mozambican artist whose artwork depicts scenes allegorical to the rising tensions and fears of the Mozambique people before and during the war. Gallery Three would exhibit several African Blackwood sculptures produced by the Makonde people of Eastern Africa, looking at how socialism may have affected both the way the artwork was made and what the art form came to represent in the coming years.

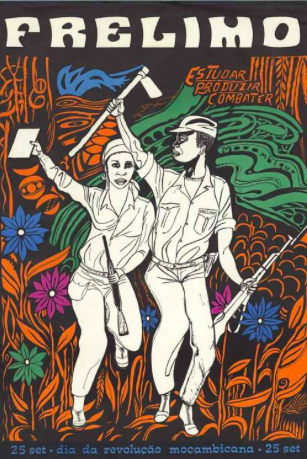

The first piece on display in Gallery One will be Commemoration of the Mozambican Revolution, designed by Agostinho Milhafre [Figure 1]. The piece was designed in 1973, nine years into the war of independence as a reminder of the unification of Mozambique against the Portuguese oppressors. In large white letters at the top of the poster the word “FRELIMO” is written. FRELIMO is an abbreviation of Frente de Libertação de Moçambique, a Mozambican liberation group that became a major player in the war for independence, producing propaganda, recruiting civilians to the cause and even engaging in guerilla warfare (a brief explanation and history of the movement should be provided within this gallery). The inclusion of both a male and female soldier show the underlying message of unity across all creeds that FRELIMO relied upon. This message is furthered by the contrast of white, monochrome soldier as compared to the bright, colorful background in which the scene is depicted.

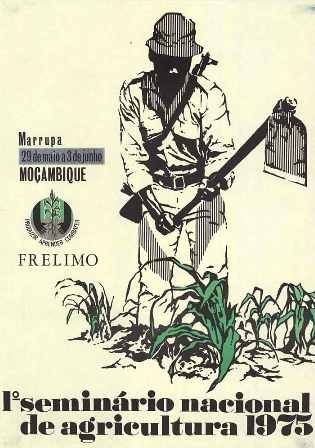

The next piece will be First National Agricultural Congress, designed by an unknown Mozambican artist [Figure 2]. This piece was produced by FRELIMO in 1975 only a few months before the war officially ended and Mozambique became an independent nation. The lack of distinct facial features on the farmer figure again portrays this ideal of uniformity and togetherness, taking design philosophies from the propaganda of other communist and socialist movements at the time, particularly that of the USSR or Maoist China. Farming and agriculture isn’t typically a mid-war concern, so the inclusion and emphasis of agriculture at this point in the war for independence may be signaling FRELIMO’s closeness to victory in addition to promoting the cohesion of Mozambique under the FRELIMO movement.

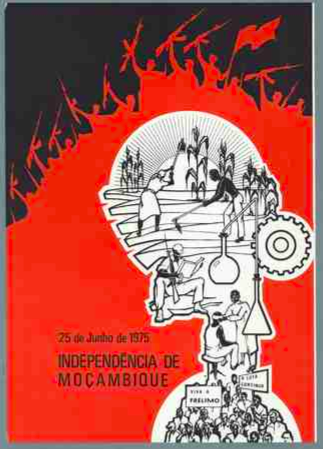

The final piece of Gallery One will be Day of Mozambique Independence designed by Jose Freire [Figure 3] in 1975 on the day of Mozambican independence, the 25th of June. At the center of this piece is a large white composition, filled with figures of workers, scientists, and other laborers for the state, including everyday citizens depicted at the base of this structure holding banners and signs promoting FRELIMO. Surrounding this composition is a large red army comprised of faceless soldiers holding their guns and banners high in victory. The emphasis on the everyday worker in the center of the image as a sort of support for the military composition is textbook socialist iconography, furthering the idea that the military and the worker are intrinsically linked, and that the success of the state relies on the success of labor. This same visual language will be revisited in Gallery Three.

The first piece of Gallery Two will be Untitled [Figure 4] produced in 1961. A multitude of overlapping figures, ranging from abstractly anthropomorphized to monstrous, depict the breakdown of the once connected Mozambique. Skulls, blood, and the aforementioned monsters are scattered throughout the work: symbols of oppression, death and murder, the fears of a tense nation on the brink of revolution. Another key feature of the work is the prevalence of crosses, a symbol of purity and holiness juxtaposed with violence and the abhorrent, a subtle criticism of the Catholic Portuguese and the establishment that allowed Mozambique to suffer.

The second featured piece will be Fountain of Blood [Figure 5], composed in 1961. In the direct center of the painting is another cross, placed below the pelvis of an abstract human skeleton, again juxtaposing Catholicism with death and decay within Mozambique. Unlike Malangatana’s other works, this piece lacks the overlapping style that his works are typically recognized by. Instead, empty, black space is much more prevalent, highlighting the relatively bright figures and blood streams. As is inferred by the title, blood is particularly focused on in this work, dripping down across the painting from various acts of dismemberment, decapitation and other graphic depictions of murder and violence, the breakdown of society as a result of human nature.

The final piece of this gallery will be Untitled [Figure 6], produced in 1967, a few years into the war for independence. In the previous works violence was depicted as a free-for-all, with both humanlike and monstrous figures committing acts of violence against the other almost mutually. However, in this piece, the violence becomes more directed. The monster figures are depicted as solely attacking and consuming the humanlike figures who, in this piece, begin to take on shapes much more similar to each other than in previous works. The three humans to the right are almost identical apart from skin color, and the three humans in the center portion of the painting have similar abstract facial features. This conflict between the human (the moral) and the monstrous (the immoral) could be allegorical to the conflict between the capitalist Portugal and the socialist Mozambique.

Gallery Three will primarily focus on the art of Makonde blackwood carvings. The Makonde are an east African ethnic group that resides along the border of Tanzania and Mozambique and thus experienced the war of independence first hand. The blackwood carvings exhibited are of the “Ujamaa” or “Dimoongo” style, brought to Tanzania in the late 1950s by artist Roberto Yakobo Sangwani, a Mozambican immigrant. The influences of socialism and the cultural changes in Mozambique on the art form make these sculptures an important aspect of east African culture in the late 20th century.

Gallery Three’s first piece will be Sculpture of three upside-down human figures carved by an unknown Makonde artist in the 20th century [Figure 7]. A common theme of Ujamaa sculpture is an inherent focus on symmetry, an aspect that this piece in particular exemplifies. Each figure is in the same position relative to each other, one hand on the ground and the other bracing the figure to the left, with their feet intermingled at the top of the piece. The piece is both physically and metaphorically stabilized by this symmetry – if one figure were to be moved out of place, the entire piece would collapse under its uneven weight, a possible allusion to the socialist philosophy of equality between all individuals. This use of the intrinsic nature of the sculptural medium to further a subtle political message is a theme that is common among the Ujamaa art form.

The next piece will be Three heads by Saidi Hanusi [Figure 8], carved in 1975. What makes this piece distinct is the individuality of each carved head–each has different features in slightly different styles, a far cry from the typical uniformity of other Ujamaa sculptures. Despite their individuality, the heads are assorted in a vertical and rectangular composition, enclosing each figure within (with the exception of the top head). As with Sculpture of three upside-down human figures, the piece is carved in a

way that balances itself, with weight added at specific points to keep its center of mass relatively close to the center line–stability through unity.

The final piece of this gallery will be Tree of Life, carved by an unknown Makonde artist [Figure 9]. The piece is comprised of a multitude of small figures each connected to the next in a chain-like fashion. These small figures are in turn connected to a large, central figure. What makes this piece particularly interesting is the use of the central figure as both a static and directional object within the piece. The figure holds the rest of the piece together, anchoring the smaller figures to the base, and yet the piece has a directional asymmetry to it–it leans into the central figure giving the piece a vector. The emotive quality of the central figure’s face as opposed to the simplistic facial features of the smaller figures hints at the central figure’s nature as a non-physical entity, potentially a characterization of community or socialism itself. This is supported by the central figures role as an anchor within the piece, holding together the collective.

Furthermore, both Tree of Life [Figure 9] and Day of Mozambique Independence [Figure 3] share similarities in their composition. Both sculptures have a central figure or shape which rests at the center of the piece which is then surrounded by a large group of smaller or less detailed figures. Whether this is coincidence or not isn’t known, however, these similarities exhibit the presence of an artistic shorthand or style that both propagandists and individual carvers noticed and utilized to further their own agendas. This leads into the exhibition’s key conclusion–that the artwork of Mozambique and Tanzania evolved to reflect the political and social changes of the time, and that this reflection was used to voice sociopolitical opinions and agendas by either the artist themselves or those who controlled its distribution. It is important to recognize that artwork can change over time, and typically it does so in response to outside factors that can affect our perception of said art. Although this exhibition will focus solely on the art of Eastern Africa, this is a conclusion that we hope visitors of this exhibition will take away and use when thinking of other forms of art from different cultures, including that of Europe or the Americas.

The accompanying powerpoint can also be accessed here: http://wheatonarthiverevue.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Art-from-War-2.pptx